A Genetic Tale: Our Diversity, our Evolution, our Adaptation

Inaugural lecture delivered at the Collège de France on Thursday 6 February 2020

Mr President of the French Academy of Sciences,

Ms

Permanent Secretary of the French Academy of Sciences,

Chairpersons

and Chief Executive Officers of research organizations,

Mr

Administrator,

Dear Colleagues, Dear Friends,

Ladies and

Gentlemen,

The question of the origins of our species, Homo sapiens, has haunted humans ever since they first appeared on Earth, and they have sought to answer it through religion, philosophy, art, history and science. When and where did “anatomically” modern humans first appear? How did our species manage to people every continent in just 60,000 years and adapt to such varied environments? Today’s human beings are characterized by a great deal of cultural and biological diversity, which may, at least partly, reflect the different mechanisms our ancestors developed to adapt to the widely diverse environments encountered through their journey across the globe.

The biological diversity of humans is immense: from our physical appearance to our various abilities to digest certain foods, our relationships with pathogens, and our susceptibility to certain diseases. But what are the origins and factors that shape this diversity? What is the respective contribution of environmental and genetic factors to the phenotypic diversity observed in humans today? How do natural selection and the demographic history of our species shape the genetic diversity of human populations? The aim of my inaugural lecture is to show how all these questions are being tackled using evolutionary and human genomic approaches.

By choosing to create the Chair of Human Genomics and Evolution, the Collège de France is recognizing the importance of population genetics, the discipline I have the honour of representing today. I am not unaware of the scale of the task. This Chair is part of the history of research and teaching at the Collège de France, at the crossroads of disciplines as varied as genetics, anthropology, immunology and medicine. These disciplines were represented here by, among others, François Jacob, Jacques Monod, Pierre Chambon and Christine Petit, for genetics; Jacques Ruffié and Yves Coppens, for anthropology; and Jean Dausset, whom I will talk to you about later, for immunology and medicine. These illustrious scientists laid the foundations of these disciplines, enabling me to summarize them today.

I am particularly grateful to the Faculty for taking the decision to create this Chair. I would particularly like to thank Alain Prochiantz for supporting its creation and Alain Fischer for defending it so well. I would also like to thank Hugues de Thé, Philippe Sansonetti and Jean-Pierre Changeux for their advice and support, as well as Vinciane Pirenne-Delforge for her invaluable help in ensuring the quality of the French in this inaugural lecture.

Population genetics studies healthy individuals, not sick individuals; it studies human populations, people like you and me, all descendants of the first humans who left Africa, descendants of those who survived famines and who resisted numerous diseases, such as tuberculosis, the Black Death or Spanish flu. The study of the genetic diversity of these individuals is at the heart of population genetics. And it is this kind of genetically rooted history, based on human biological diversity, that we want to use to help us understand our history, our evolution, our adaptation to the environment, and even our diseases.

This quest for diversity can be traced back to Francis I, who summoned Leonardo da Vinci to his court, bearing the three jewels now on display in the Louvre: The Virgin, Child Jesus and Saint Anne, Saint John the Baptist, and the Mona Lisa (Fig. 1). François I, inspired by his sister Marguerite de Navarre, was also responsible for the creation of the Collège de France. This taste for diversity still characterizes the guiding principles of this institution, the former Collège Royal, whose lecturers were responsible for teaching subjects that had previously been overlooked by the University of Paris, such as Greek, Hebrew and philosophy. The motto docet omnia reflects this diversity, which Pierre Corvol, the former Administrator of the Collège de France, further emphasized when he said: docet omnes omnia (it teaches everything to everyone).

Leonardo da Vinci, The Virgin, the Child Jesus and Saint Anne, Saint John the Baptist, and the Mona Lisa, 16th century, oil on wood, Musée du Louvre, Department of Paintings.

Darwin and Mendel: the origins of population genetics

The Chair that I have the honour and pleasure of inaugurating brings together two disciplines, genetics and evolution. These disciplines were founded separately, in the mid-nineteenth century, by Gregor Mendel and Charles Darwin. It took many decades for biologists to establish a link between the principles of heredity and the processes underlying evolution. Yet thinkers since Antiquity appear to have defended the idea that an organism could change into another organism. Anaximander of Miletus claimed that the first animals lived in water and that land animals evolved from them, and Empedocles affirmed that living beings did not have a supernatural origin. However, the fact that philosophers as influential as Plato and Aristotle argued in favour of the divine origin of living beings, and the subsequent 2,000 years of Christianity, prevented the emergence of evolutionary thinking before the early nineteenth century, despite a few advances by Enlightenment thinkers.

It was the Frenchman Jean-Baptiste Lamarck who first formulated a theory of evolution in his book Philosophie zoologique, where he argued that organisms appear spontaneously and evolve towards a higher level of complexity under the pressure of their environment. However, after the Congress of Vienna and his death in 1829, there was no mention of evolution until Charles Darwin. In 1859, fearing that Alfred Russel Wallace would publish the same idea as his own, namely evolution by natural selection, Darwin published his masterpiece The Origin of Species. In this book, he developed the notion of “adaptation” to the environment and set out the extraordinary intuition that, if this adaptation is inherited, the proportion of individuals that survive in a specific environment will change over the generations. The book was a stunning success, selling over 1,000 copies on the first day. The violent reactions were no less exceptional, especially from the Anglican Church. Darwin recognized Wallace’s merits and, after the publication of his book, he led a solitary life in Kent, wounded by the reactions and controversy it had provoked. He died in 1882 at the age of 73.

It was with the Czech abbot Gregor Mendel, a contemporary of Charles Darwin and the founding father of genetics, that Darwin’s concept of “heritability” became a reality, with the publication in 1865 of his work on the transmission of hereditary traits. Ten years of experiments carried out on thousands of peas resulted in Mendel’s laws, which defined the way in which genes, which he called “factors”, are transmitted from generation to generation. In 1889, the Dutch naturalist Hugo de Vries proposed the term pangene to denote the physical unit of character transmission, and later, at the beginning of the twentieth century, the Danish botanist, physiologist and geneticist Wilhelm Johannsen introduced terms such as genetics and gene. Unfortunately, Mendel’s seminal paper was not at all successful, and Darwin never read it. The link between heredity and evolution had yet to be made.

The reconciliation of Darwinism and Mendelism was initiated by young researchers from Francis Galton’s British school of biometrics: Ronald Fisher, who laid the foundations of quantitative genetics; Sewal Wright, known for his concepts of “adaptive landscape” and “genetic drift”; and John B.S. Haldane, who was interested in the interactions between natural selection, mutation, and gene flow. All three founded population genetics, a discipline that combines evolution and genetics into a coherent mathematically-modelled framework.

Although Fisher, Wright and Haldane were the founders of theoretical population genetics, it was with Ernst Mayr, Theodosius Dobzhansky and Julian Huxley that an interdisciplinary consensus emerged, known as the “synthetic theory of evolution” – a neo-Darwinian theory based on the natural selection of random variations in the genome. This theory established the legitimacy of evolutionary biology, and natural selection became the only acceptable mechanism for explaining evolutionary changes.

It was with the advent of molecular biology in the mid-twentieth century that the understanding of the nature of hereditary inheritance, thus of DNA, emerged. The discovery of the structure of the double helix molecule by Francis Crick, Rosalind Franklin and James Watson was unquestionably a major breakthrough in biology, giving the scientific community one of the keys to understanding the secrets of life. Two pioneers of molecular biology, the Frenchmen Jacques Monod and François Jacob, both professors of the Collège de France and winners – together with André Lwoff – of the Nobel Prize in 1965, coined the concept of the “operon”. An operon is a unit made up of several genes whose expression is regulated by a single promoter – a notion also attributed to these two French scientists.

It was thanks to all these discoveries in molecular biology and, more generally, in genetics, that the Japanese scientist Motoo Kimura was able to combine theoretical approaches with empirical data, and proposed the neutralist theory of evolution (Kimura, 1968). According to this theory, most evolutionary changes are due to genetic drift, that is, a random process independent of natural selection and migration. However, the neutralist theory primarily refers to evolution at the molecular level, and Kimura himself recognized that phenotypic evolution cannot take place without the action of natural selection.

Human genome sequencing and the quest for diversity

Studies in genetics developed rapidly with the advent of DNA sequencing techniques and, above all, the sequencing of the human genome, which was completed in the early 2000s. This sequence provided key insights into the structure and content of the genome. We now know that it is made up of around 3.1 billion nucleotides and that each individual, with the exception of monozygotic twins, has their own, unique genome. We also know that our human genome contains around 20,000 protein-coding genes, proteins being the essential building blocks of a living being, and that the majority of the genome (98%) is noncoding and is largely involved in regulatory functions.

The sequencing of the human genome nevertheless provided very little information about the extent of genetic diversity between individuals or populations, since it mostly involved a single sequence. It was with the advent of new genomic technologies, such as DNA chips and next-generation sequencing, combined with the decrease of sequencing costs, that the study of human genome diversity entered its golden age. Several international consortia were set up to characterize human genetic diversity across multiple populations worldwide, thus facilitating studies in population genetics and medical genetics. Thanks to them, we now know that each of us carries 250 to 300 loss-of-function gene variants, raising questions about the levels of redundancy in the genome (Auton et al., 2015). We also know that we are all born with 50 to 100 mutations, fortunately in the heterozygous state, associated with genetic diseases.

These genomic studies have also increased our understanding of the demographic and adaptive history of human populations, how our ancestors admixed with other, now-extinct human forms such as Neanderthals or Denisovans, and the influence of natural selection on genome diversity (Fan et al., 2016; Leonardi et al., 2017; Nielsen et al., 2017; Quach and Quintana-Murci, 2017; Skoglund and Mathieson, 2018; Vitti et al., 2013). These studies have also provided invaluable knowledge for the clinical interpretation of genetic variants identified in patients and for dissecting the genetic architecture of morphological and physiological traits.

It is in this context that I would like to pay tribute to a pioneering initiative in the study of human genetic diversity: the Jean Dausset-CEPH Foundation. The CEPH is the Centre for the Study of Human Polymorphism, and Jean Dausset, a visionary, great scientist and physician, to whom I owe a great deal. I had the fortune and honour of knowing him personally and learning a great deal from him during our discussions, both in Majorca, my native island where he had settled, and in his Paris flat, just across from the cour d’honneur of the Collège de France. I will never forget him and I dedicate this inaugural lecture to him with my deepest affection.

With Jean Dausset’s support, Howard Cann, an American paediatrician and member of the Foundation, in collaboration with Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza of Stanford University, set up a panel comprising over a thousand immortalized cell lines from individuals from fifty-two populations around the world. Over the last twenty-five years, and despite being underestimated at national level, the CEPH has acquired a leading international reputation, since its multi-ethnic panel has made it possible to characterize the genetic diversity of our species at an unprecedented level of resolution.

Human migration and natural selection

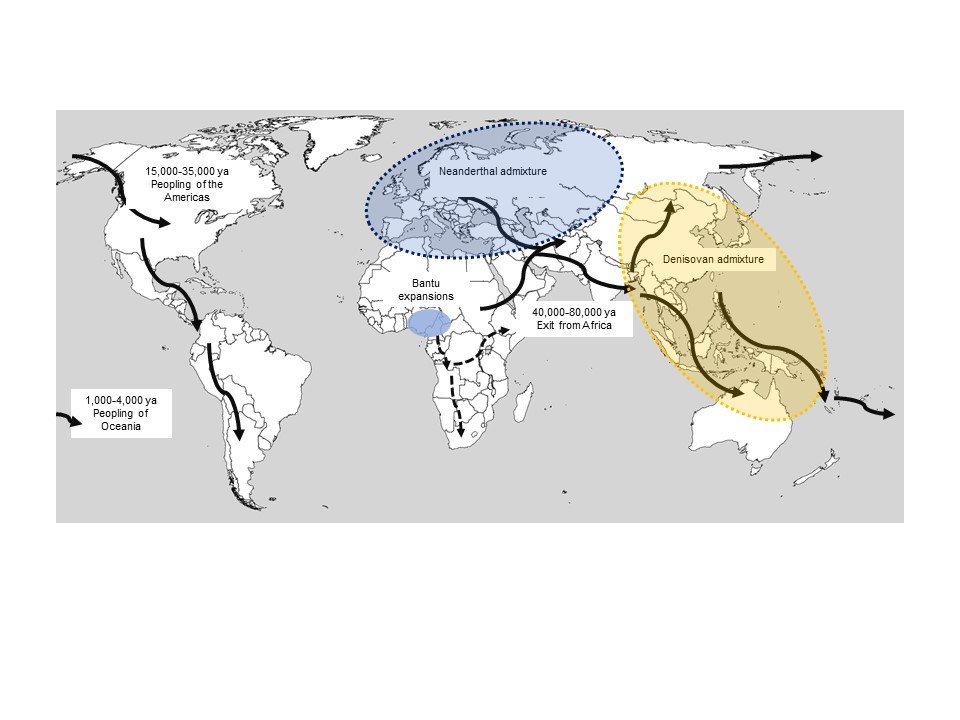

Studies in human genomics have also uncovered important information about the origins and migrations of Homo sapiens. Paleoanthropological records indicate that our ancestors appeared in Africa around 200,000-300,000 years ago, then dispersed out of Africa around 60,000 years ago, rapidly colonizing Eurasia and Australia (Nielsen et al., 2017). Humans ultimately reached more distant locations, such as the Americas, around 15,000-35,000 years ago, and then the remote islands of Oceania, where they settled as recently as 1,000-4,000 years ago (Fig. 2).

The major human migrations across the planet: approximate habitat areas of Neanderthals and Denisovans. The expansion of the Bantu-speaking peoples, which began around 4,000-5,000 years ago, is indicated by arrows on the African continent.

Genetics has also revealed a great deal of substructure of populations within continents. In sub-Saharan Africa, population genetic structure is correlated with geography, the distribution of language families, and modes of subsistence, whereas in Europe genetic diversity is strongly driven by geography, with population structure being detectable within even small areas about 500 km apart (Novembre et al., 2008).

Alongside the analysis of so-called “neutral” genomic regions, which inform past demographic events, the detection of the signatures of natural selection in the genome makes it possible to reconstruct our adaptive history, that is, the ways in which humans have biologically adapted to their environment (Fan et al., 2016; Jeong and Di Rienzo, 2014; Novembre and Di Rienzo, 2009). Although the shaping of population genetic diversity is primarily driven by genetic drift, natural selection also influences genetic diversity and can take varied forms (Vitti et al., 2013).

The most widespread form of selection in our genomes, purifying selection, eliminates deleterious alleles from the population, while positive selection acts on mutations that are advantageous for our survival, according to different evolutionary models. In the classic selective sweep model, positive selection acts upon a newly arising advantageous mutation that will rapidly increase in frequency in the population. Polygenic selection, on the other hand, involves the simultaneous selection of numerous variants on numerous genes, each making its own small contribution to better adaptation. Genetic adaptation can also be achieved through balancing selection, which preserves functional diversity through heterozygote advantage, frequency-dependent selection or pleiotropy. Each form of selection leaves very specific molecular signatures around the selected region (Vitti et al., 2013).

Recent studies have led to a better understanding of the ways in which population history influences the efficacy of purifying selection (Henn et al., 2015; Lohmueller, 2014). European populations, for example, have a higher proportion of deleterious variants than African populations – a pattern that is consistent with less purging of deleterious alleles in smaller populations, where the effects of genetic drift are more pronounced. Similarly, populations resulting from strong founder effects, such as the French Canadians, or having experienced bottlenecks, such as the Finns, have an even higher proportion of deleterious variants, including some associated that lead to the complete inactivation of certain genes.

Conversely, the occurrence of positive selection informs the adaptive potential of our species (Fan et al., 2016). During their long journey across the globe, humans have had to adapt to a wide variety of climatic, nutritional and pathogenic conditions. In recent years, the study of positive selection on the genome has proved crucial in identifying some key genes involved in the morphological and physiological diversity of human populations. Iconic cases of positive selection are variants in the lactase gene (LCT), responsible for the persistence of lactose tolerance in adults (Tishkoff et al., 2007). Other examples include genes involved in the variation of skin pigmentation and adaptation to cold, to rainforests environments or to life at high altitudes in hypoxic conditions (that is, the lack of oxygen supply to the body’s tissues) (Fan et al., 2016). As we will see later, positive selection has also targeted genes involved in immune response and resistance to infectious diseases (Quach and Quintana-Murci, 2017; Quintana-Murci, 2019).

A long history of archaic and modern admixture

The possibility of sequencing DNA from fossil remains has been a scientific revolution over the last decade (Leonardi et al., 2017; Skoglund and Mathieson, 2018; Stoneking and Krause, 2011). The study of the DNA of hominins such as Neanderthals and Denisovans, present in Eurasia until around 40,000 years ago, has shown that our species, Homo sapiens, did admix with these ancient humans (Racimo et al., 2015) (Fig. 2). This phenomenon, known as archaic introgression, can be observed in the genome of modern human populations; at a rate of 2% for Neanderthal ancestry in the genome of Eurasians, and up to 5% for Denisovan ancestry in certain Pacific populations (Sankararaman et al., 2014). In most cases, there has been strong selection against archaic introgression, particularly among protein-coding genes, probably due to its deleterious effects in modern humans. Identifying regions of the human genome strongly depleted of archaic ancestry makes it possible to identify functions that may have contributed to the uniqueness of certain Homo sapiens traits.

Modern humans have however also acquired advantageous alleles through this ancient admixture, via a process known as adaptive introgression. For example, certain variants of the HLA (human leukocyte antigen) immune system, discovered by Jean Dausset and for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1980, were acquired through admixture of early Eurasians with Neanderthals (Abi-Rached et al., 2011). Another significant example: the EPAS1 gene, associated with the response to hypoxia, displays a high degree of Denisovan ancestry in Tibetans, suggesting that this population acquired advantageous alleles for life at high altitude through admixture with Denisovans (Huerta-Sanchez et al., 2014). Our most recent work shows that admixture with both Neanderthals and Denisovans may also have enabled our ancestors to better survive life-threatening infectious diseases (Quintana-Murci, 2019).

Unlike archaic introgression, the role of admixture between modern populations in their adaptation to the environment remained largely unknown. The study of the genome diversity in over ninety human populations has shown that admixture has been a pervasive feature in our species (Hellenthal et al., 2014). Classic examples of admixture between populations are those associated with the expansion of the Mongol Empire in Eurasia and the Bantu languages in Africa. More recently, and for unfortunate reasons relating to slave-trade, we can mention the admixture between European settlers and slaves of African ancestry, leading to contemporary African-Americans. Cutting-edge statistical methods now make it possible to decompose the genomes of admixed populations into segments of different ancestry, which in turn makes it easier to identify the genetic variants associated with the risk of developing certain diseases.

We have only recently begun to study how modern admixture might also have facilitated human adaptation (Patin et al., 2017). This phenomenon, which we have termed adaptive admixture, had not until now been systematically tested in humans, even though it could represent a major asset in our evolution. The aim is to identify regions of the genome that, as a result of admixture, show an excess of inheritance from a parental population, compared with genomic expectations.

The history of Homo sapiens through the lens of evolutionary genetics

Over the past twenty-five years, the federating element of my research has been the study of the genetic diversity of human populations, which can be broken down into three main areas: understanding the demographic history of our species; understanding the history of human adaptation to their environment, in particular to the microbial environment; and finally, understanding the nature of the factors responsible for the variability of our immune system (Quach and Quintana-Murci, 2017; Quintana-Murci, 2016; Quintana-Murci, 2019). To this end, our laboratory combines population genetics and cellular genomic approaches, with computational modelling and development of new statistical frameworks.

At this point, I would like to thank the real players in this research, those who have been with me since the beginning and those who have joined me more recently; in short, all those who have contributed or are still contributing to this great team adventure. It is a privilege for me to be able to work with such people. I would also like to thank the Institut Pasteur and the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) for their kindness and for having encouraged and supported us from the beginning, as well as funding agencies and foundations, with special thanks to the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (FRM). Finally, I would like to reserve a special mention for the person who, de facto, co-directs the laboratory with me, my teammate Étienne Patin, a brilliant, generous, altruistic man who always puts the scientific question to be solved before all else.

Study of the demographic history of human populations

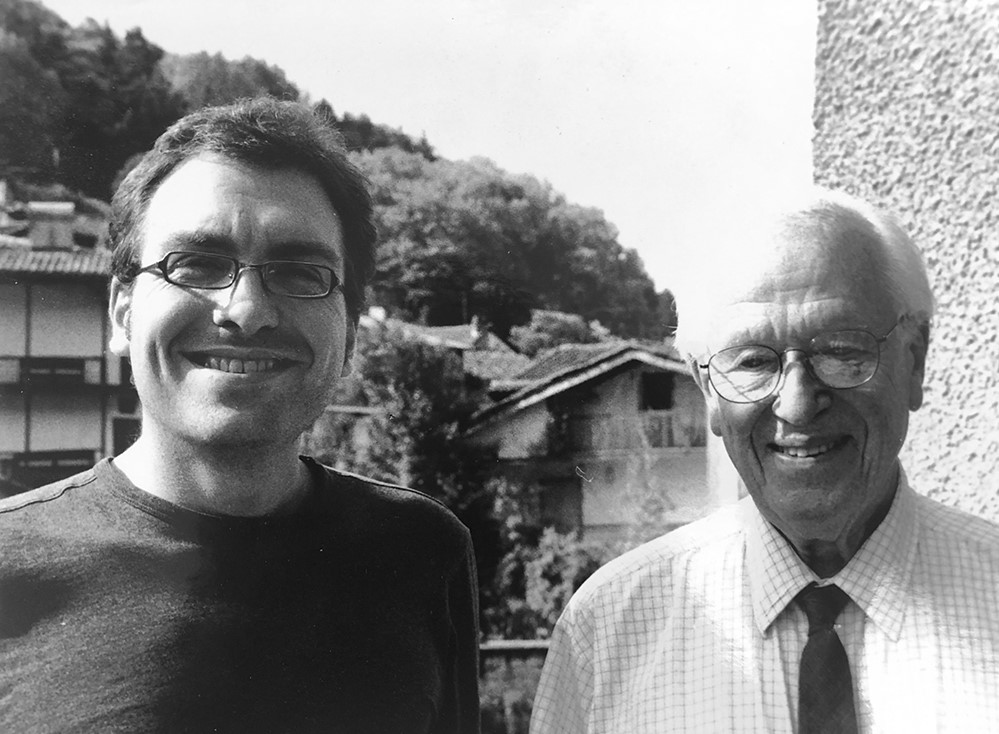

Let us turn now to the first line of research: estimating the demographic parameters that characterize the history of human populations and their migrations. When I was doing my PhD in Italy in the 1990s, an inexhaustible source of inspiration in this area was my discussions with Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza (Fig. 3), a Stanford University professor, relentless Africanist and the indisputable father of modern human population genetics. He created a veritable school of thought and divided his time between the United States and Pavia, where I was able to benefit from his knowledge.

Portrait of Lluis Quintana-Murci and Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza, father of modern population genetics and author of the book La Génétique des populations : histoire d’une découverte, co-written with Francesco Cavalli-Sforza, Paris, Odile Jacob, 2008.

Credit: Franz Manni, late 1990s.

Since, at the time, we could not work at the scale of the entire genome, we focused our attention on the use of uniparentally-inherited markers, that is, mitochondrial DNA, inherited from the mother, and the Y chromosome, inherited from the father. Using mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), we provided genetic evidence that Homo sapiens left Africa 60,000 years ago following a southern, coastal route from East Africa to South Asia (Quintana-Murci et al., 1999). This work on the phylogeography of African populations laid the foundations for many other studies in this field. For example, the study of mtDNA and the Y chromosome in populations residing on the Iranian plateau and the Indus valley enabled us to show that this region had an extremely complex genetic history, including founder effects, sexually-asymmetric admixture events and remnants of the Indian Ocean slave trade (Quintana-Murci et al., 2004). Similar phylogeographic approaches also increased our understanding of the origin of the Basques – a non-Indo-European-speaking population considered to be a linguistic isolate – and, more generally, the role of the Franco-Cantabrian refuge in the post-glacial repopulation of Europe. Although most of their genetic diversity is shared with their non-Basque-speaking neighbours, our data supported the hypothesis of a partial genetic continuity between contemporary Basques and the inhabitants of the Franco-Cantabrian region during the Palaeolithic and Mesolithic periods (Behar et al., 2012).

Modes of subsistence, migrations and adaptation to the environment

One of the main interests of my laboratory has been to study the impact of modes of subsistence on population genetic diversity. Over the past 10,000 years, different communities across the globe embarked on an unprecedented technological and cultural revolution. They abandoned a subsistence lifestyle based on hunting and gathering, to develop agriculture and animal husbandry (Diamond and Bellwood, 2003). This transition increased the biogenic capacity of farmers’ environments and led to changes in the chemical, nutritional and pathogenic environment. The development of agriculture, for example, facilitated the transmission of certain infectious agents, with animal domestication increasing exposure to new zoonoses.

In this context, Central Africa represents a particularly informative region. First, this region was the scene of one of the largest population movements in African history: around 4,000 years ago, the emergence of agriculture marked a decisive turning point. Having mastered this new technology, which enabled them to move into new territories, the Bantu-speaking peoples gradually extended their area of habitat and, over the course of several millennia, settled throughout all sub-Saharan Africa (Phillipson, 1975). Second, Central Africa is the homeland of the largest living group of active hunter-gatherers in the world: the rainforest hunter-gatherers, historically known as “Pygmies” (Cavalli-Sforza, 1986) (Fig. 4). Not only do these two groups have different modes of subsistence, they also differ in terms of their ecotope and the prevalence of some diseases.

Pygmy woman from Uganda, Nsua ethnic group from Mulimassenge village (Bundibugyo district, Uganda). Credit: Paul Verdu, September 2007.

Over the last fifteen years, in close collaboration with Paul Verdu and many researchers from the Musée de l’Homme, as well as Antoine Gessain from the Institut Pasteur and Jean-Marie Hombert from the University of Lyon, we have learned a great deal about the history of these populations, from the time when they diverged from each other, to their changes in population size and the history of admixture (Patin and Quintana-Murci, 2018). For example, using maximum-likelihood methods, we showed that the ancestors of contemporary farmers and rainforest hunter-gatherers diverged at least 60,000 years ago (Lopez et al., 2018; Patin et al., 2009). Our studies have also shown that the ancestors of rainforest hunter-gatherers experienced a major bottleneck less than 20,000 years ago, whereas the ancestors of farming populations entered a period of strong, demographic expansion at least 8,000 years ago (Patin et al., 2014). These results support the hypothesis that the ancestors of farmers were already a demographically flourishing population well before the emergence of agriculture, around 4,000 years ago. Our studies have thus called into question the impact of agriculture on the African “Neolithic” history; agriculture appears not to have been the direct cause of the demographic success of the populations that adopted it (Patin et al., 2014).

But what impact have these demographic differences had on the proportion of deleterious mutations carried by these populations? In other words, what influence have they had on the “genetic burden” of these groups? Genetic drift would lead us to expect Pygmies to have accumulated a higher proportion of deleterious mutations than their farming neighbours whose populations were expanding. However, we have been able to show that individuals from both populations carry on average an equivalent number of deleterious variants (Lopez et al., 2018). Recent admixture between the two populations thus seems to have homogenized the differences in their respective burdens of deleterious mutations. It would therefore be interesting to study the impact of migration and admixture on the mutational load, which should ultimately lead to a better understanding of the genetic architecture of human diseases.

Our studies on the genetic history of Africa have also focused on reconstructing the migratory history of Bantu-speaking peoples (Patin et al., 2017) (Fig. 2), who currently number more than 300 million speakers. The question of the migratory routes taken by these peoples remained poorly known: while an initial theory, known as the “early split”, asserted that the Bantu, on leaving their original cradle, had split up from the outset into two movements, towards the east and the south, the “late split” hypothesis suggested that they had first crossed the equatorial rainforest before splitting up into two migratory flows. Through a genomic study of more than 2,000 individuals from fifty sub-Saharan African populations, we provided support to the late split hypothesis: Bantu-speaking peoples are most likely to have first crossed the equatorial rainforest before splitting towards the east and the south (Patin et al., 2017).

As Bantu-speaking groups spread across sub-Saharan Africa, they systematically admixed with autochthonous populations, such as rainforest hunter-gatherers in Central Africa, pastoralists in East Africa and Khoisan hunter-gatherers in the Kalahari Desert. This admixture seems to have been beneficial to Bantu-speaking peoples, enabling them to acquire advantageous mutations that facilitated their adaptation to new habitats they encountered (Patin et al., 2017). We have highlighted two remarkable examples of adaptive admixture: from their admixture with rainforest hunter-gatherers, western Bantus acquired advantageous variants of the HLA immune system, and from their admixture with East African pastoralists, eastern Bantus acquired a form of the lactase gene, which enables the digestion of milk in adulthood.

But our most recent work, in collaboration with Franck Prugnolle and François Renaud of the CNRS in Montpellier, has shown that this admixture was also beneficial for rainforest hunter-gatherers (Laval et al., 2019). We have revisited one of the most emblematic cases of balanced selection, namely the HbS mutation in the beta-globin gene in Africa. In the heterozygous state, this mutation increases protection against malaria, although in the homozygous state it causes sickle-cell disease. Since, in the absence of malaria, the mutation would disappear in around twelve generations, dating the age of appearance of this mutation should provide us with information about the time when malaria appeared. Using state-of-the-art Bayesian methods, we have shown that the HbS mutation appeared in the ancestors of African farmers more than 20,000 years ago, suggesting that these populations were exposed to malaria much earlier than previously thought. The mutation was subsequently acquired by rainforest hunter-gatherers through adaptive admixture with neighbouring farmers, over the last 6,000 years.

Malaria has been a major cause of mortality throughout our history, generating unprecedented selection pressure. The adaptive nature of the so-called “null” mutation in the DARC gene, a variant of African origin that protects against Plasmodium vivax malaria, has also been detected in the context of adaptive admixture (Laso-Jadart et al., 2017). This mutation has a frequency of 50% in the Afro-Pakistani Makrani population, whereas their genomes show, on average, only 17% African origin. These results seem to indicate that the null mutation has conferred a strong selective advantage on the Makrani, in a region of Pakistan where Plasmodium vivax is endemic. All these examples underline once again the importance of admixture as a vehicle for human genetic adaptation to the environment.

The diversity of modes of subsistence among African populations is accompanied by a certain phenotypic diversity, which suggests a different adaptation to the environment. In particular, rainforest hunter-gatherers have a short stature, which has been considered to be the result of adaptation to life in the rainforest. To identify genes and traits under selection in rainforest hunter-gatherers, we analysed a large genomic dataset from different rainforest hunter-gatherers populations in Central Africa (Lopez et al., 2019). A very strong positive selection signal shared by all rainforest hunter-gatherers groups was identified for a single gene (TRPS1), which is involved in various morphological and immune traits. Our analyses also showed that genes associated with height displayed an excess of polygenic selection signals in rainforest hunter-gatherers. We know that these genes have pleiotropic effects on other traits, such as body mass and age at sexual maturity. However, our results suggest that it is precisely height, and not other life-history traits, that is the true phenotype under natural selection in African rainforest hunter-gatherers.

Reacting to the environment: epigenetics in human populations

In addition to genetic adaptation, humans, like other organisms, have other ways of responding to environmental pressures. These include epigenetic changes, defined by our colleague Edith Heard, a world expert in the field, as “any change in gene expression that does not involve a change in the DNA sequence”. In other words, the genome refers to all the material carrying genetic information (DNA in humans), while the epigenome refers to the epigenetic state of the cell, that is, all the non-genetic factors regulating gene expression. DNA methylation is perhaps the best understood component of the epigenetic machinery (Smith and Meissner, 2013). Although the relationship between DNA methylation and gene expression is complex, overall there is a negative correlation between the two: the more the promoter of a gene is methylated, the less the gene is expressed.

But what factors affect DNA methylation variation? On the one hand, methylation can be altered by DNA sequence variations, which means that it depends, in part, on genetics itself. On the other hand, environmental factors can have a major impact on the variability of methylation profiles. Exposure to sunlight, smoking, nutrition, certain therapeutic treatments, stress or even the social environment can affect our methylation profiles and thus the expression of some genes. For example, two twins share exactly the same genome, but their epigenome will become increasingly different over the course of their lives, depending on exposure to their environment or simply different life experiences. We have shown, for example, that there can indeed be a significant difference between human populations in terms of their epigenome (Husquin et al., 2018). The diversity of epigenetic profiles could therefore explain a significant proportion of human phenotypic variations.

In order to understand the impact of lifestyle and habitat on DNA methylation variability in humans, Central Africa once again provides an ideal field of study, as it is home to populations that differ in terms of their habitat (forest or urban/rural areas) and lifestyle (hunter-gatherers or farmers). Our work indicates that immune functions are particularly affected by changes in habitat, as shown by the different epigenomes of forest and urban populations (Fagny et al., 2015). Conversely, if the habitat remains constant, developmental processes are the most affected, as witnessed in the epigenetic differences observed between farmers and hunter-gatherers living in the forest. It turns out that these latter differences are largely due to genetic variants, many of which evolve under positive selection. These results suggest that human populations can respond “epigenetically” to environmental changes, highlighting some phenotypic plasticity. Over time, genetic changes can appear and stabilize phenotypes, enabling them to adapt to the environment in a more sustainable way.

In the context of genetic adaptation to the environment, one of our major discoveries has been to show that Darwinian positive selection has increased differences between human populations (Barreiro et al., 2008), mainly targeting genetic variants that alter the protein sequence or are located in regulatory regions. We have identified several genes that have most likely played an important role in the differentiation of major population groups in Africa, Europe and Asia. These genes are involved in phenotypic traits that vary between populations, such as skin pigmentation, metabolic syndrome (hypertension, obesity and diabetes) and immune response.

Humans and microbes: a double-edged relationship

The link between natural selection, immune response and infectious diseases has been the second major focus of our research. Humans and microbes have a longstanding, double-edged relationship (Siddle and Quintana-Murci, 2014). They can complement each other and maintain a state of homeostasis, as in the gut microbiota, for example, but microorganisms can also sometimes be pathogenic, causing disease. Just as famine and war have continually inflicted a massive mortality burden on humans, so too has the threat of pathogenic infections had an overwhelming effect. Ancient diseases such as malaria and tuberculosis, or more recent ones such as the Black Death and Spanish flu, have killed millions of people throughout human history.

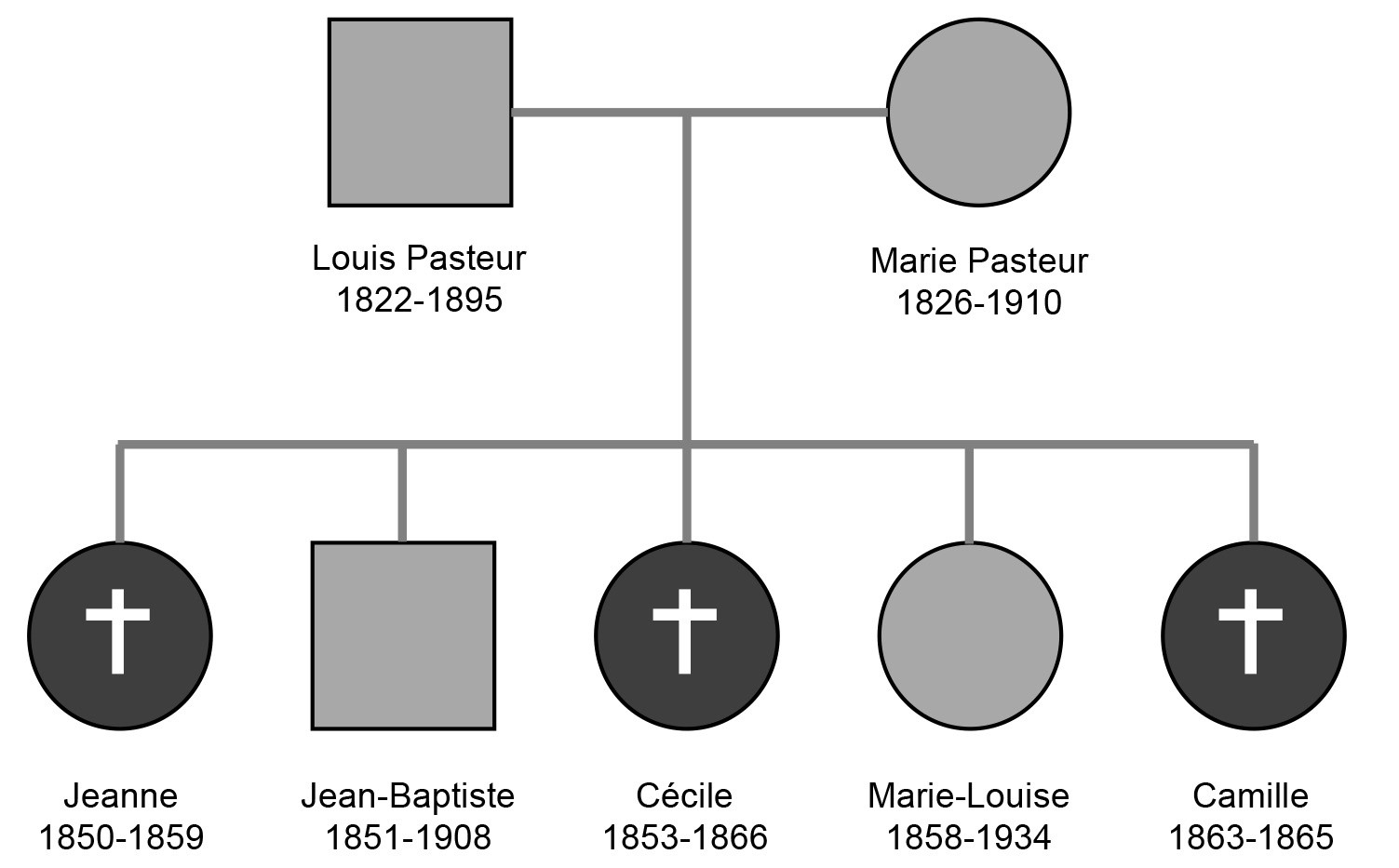

Mortality rates from infection remained high until the late nineteenth century, when hygiene improved and vaccines and antibiotics began to be developed (Cairns, 1997; Casanova and Abel, 2005). At the end of the nineteenth century, for example, only 35% of Europeans reached the age of 40, illustrating the heavy burden of infection and the harsh law that had prevailed until then in the history of our species. Even Louis Pasteur, the father of the microbial theory, lost three of his daughters to what was then known as “fever”. Retrospectively, it is tempting to speculate that they died of an infectious disease (Fig. 5). This illustrious family is representative of most families at the time: it was not uncommon for at least half the siblings in a family to die of infection. The question that arises from this observation is: why this half? In Pasteur’s family, one son and one daughter survived into adulthood, although they had probably been exposed to at least one of the microbes that killed their sisters. It is therefore possible that the three daughters who died carried some form of genetic predisposition to infectious disease.

Louis Pasteur’s family pedigree. Louis Pasteur, the father of the microbial theory, lost three daughters to “fever”. In retrospect, it is possible that they carried some form of genetic vulnerability predisposing them to infectious diseases.

The first to establish a causal link between mortality, infectious diseases and natural selection were John B.S. Haldane and Anthony Allison, in the 1950s. They hypothesized that red blood cell disorders, such as thalassaemia and sickle-cell disease, could provide protection against malaria (Allison, 1954; Haldane, 1949). Since that early work, a growing number of population genetics studies have shown that genes involved in immune functions display among the strongest signatures of natural selection of the genome, underlining the major role played by pathogens in the evolution of our species.

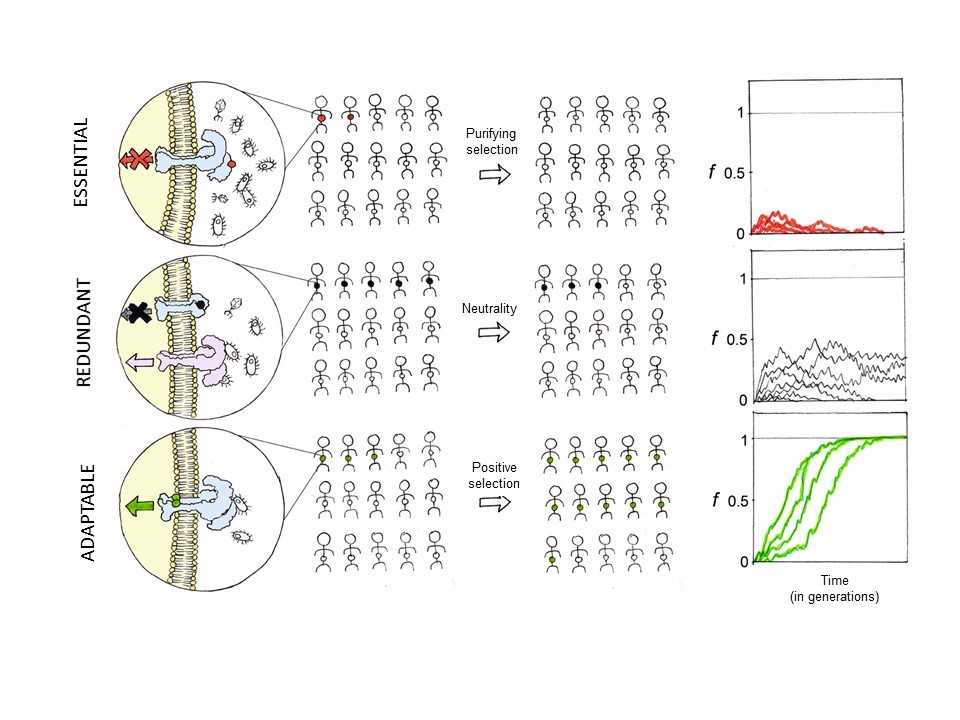

It was with these questions in mind that, around fifteen years ago, through Philippe Kourilsky, Professor of the Collège de France and, at the time, Director of the Institut Pasteur, I had the good fortune to meet Jean-Laurent Casanova and Laurent Abel. Together, we pioneered a new multidisciplinary approach to the study of infection, integrating clinical genetics, epidemiological genetics and evolutionary genetics (Alcais et al., 2010; Casanova et al., 2013; Quintana-Murci, 2016; Quintana-Murci, 2019). The detection of the molecular signatures of selection in genes involved in immunity, or the absence of such signatures (neutrality), combined with clinical and epidemiological data, has enabled us to assess the biological relevance of the corresponding genes in natura and to determine whether they are essential, redundant or adaptable (Fig. 6).

Natural selection and the biological relevance of immunity genes. In essential genes, mutations are purged from the population through purifying selection, and their frequencies (f) remain low in the general population. Redundant genes can accumulate mutations, even in some cases deleterious, that reach non-negligible frequencies in the population because they evolve under neutrality. Finally, mutations in “adaptable” genes can increase in frequency in the population because they confer an evolutionary advantage for better survival in the face of infectious agents.

Natural selection, innate immunity and collateral damage

One of our main interests has been to study the evolution of innate immunity genes, that is, the first line of host defence against pathogens (Barreiro and Quintana-Murci, 2010; Quintana-Murci and Clark, 2013). These studies have enabled us to establish a hierarchical model of the different families of microbial receptors according to their biological relevance in host defence (Barreiro et al., 2009; Quintana-Murci and Clark, 2013; Vasseur et al., 2012) (Fig. 6). Evidence that genes evolving under strong purifying selection, that is, essential genes, are involved in diseases, is the fact that mutations in some of these genes – e.g. endosomal Toll-like receptors (TLRs) or interferon gamma – have been associated with life-threatening phenotypes, such as herpex-simplex encephalitis, pyogenic bacterial infections, and Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial diseases.

Strong or complete redundancy of a gene can also be inferred from population genetics data (Barreiro et al., 2009; Quintana-Murci and Clark, 2013). For example, we found strong redundancy for the TLR5 receptor, where a loss-of-function variant reaches high frequencies of around 10% in Europe and 30% in North Africa in the general population. This shows that the function of the TLR5 receptor, which is to recognize flagellated bacteria, is a redundant function, since in the absence of this receptor, other molecules will have the same function. In rare cases, loss-of-function mutations may not only be tolerated, but may actually prove beneficial. This has been observed for variants in the CASP12, DARC and FUT2 genes, which have increased in frequency in the population because they provide protection against sepsis, vivax malaria and norovirus infections, respectively.

Mutations that improve the effectiveness of the immune response can, in some cases, rapidly increase in frequency in a given population through positive selection. For example, we have identified mutations in type-III interferons (IFNs), molecules involved in host responses to viruses, which show strong positive selection signals in Europe and Asia (Manry et al., 2011). At the more general level of the innate immunity system, we have detected more than 50 genes showing strong positive selection signals in different human populations. Moreover, these selection phenomena have probably occurred over the last 6,000 to 13,000 years (Deschamps et al., 2016), which again corresponds to the period of transition from a hunter-gatherer to a farming-based lifestyle.

However, adaptation to pathogens can sometimes result in collateral damage. In some cases, positively selected alleles do not provide protection, as would be expected, but are associated with greater susceptibility to certain diseases, such as Crohn’s disease, type-1 diabetes or celiac disease (Barreiro and Quintana-Murci, 2010; Brinkworth and Barreiro, 2014; Fagny et al., 2014). These data thus support the hygienist theory, dear to Jean-François Bach, an immunologist at Necker Hospital and member of the French Academy of Sciences (Bach, 2002; Strachan, 1989). The theory holds that, following a change in the environment, certain mutations that were advantageous in the past and enabled us to better survive infection are now associated to an increased susceptibility to autoimmune, inflammatory or allergic diseases, notably in industrialized countries where exposure to infections has been reduced.

Neanderthal ancestry and antiviral responses

Our work on the evolution of immunity has also shown that admixture between Neanderthals and our ancestors introduced genetic variants into the latter that enhanced their ability to protect themselves against infection. The first link between archaic introgression and immunity was identified in the HLA region by Peter Parham’s team at Stanford University (Abi-Rached et al., 2011). Since this pioneering study, the number of immune genes found to present evidence of beneficial archaic introgression has steadily increased (Dannemann and Racimo, 2018; Quintana-Murci, 2019; Racimo et al., 2015). For example, our work has shown that levels of Neanderthal ancestry are particularly high for innate immunity genes (Deschamps et al., 2016). We detected a very strong signature of the beneficial effects of Neanderthal introgression for TLR6-1-10 receptors, molecules involved in the recognition of microbes on the cell surface.

Some of these archaic DNA segments also have an impact on gene expression. For example, our recent work shows that regulatory variants of gene expression in monocytes – a major cell type of innate immunity – are enriched in Neanderthal ancestry, particularly those associated with the antiviral response (Quach et al., 2016). This link between Neanderthal introgression and antiviral response is supported by an even more recent study demonstrating that Neanderthal segments introduced in modern human genomes are enriched in genes encoding proteins that interact with viruses, particularly RNA viruses, such as influenza or COVID-19 viruses (Enard and Petrov, 2018). In addition, Neanderthal introgression specifically affected distal regulatory regions, the enhancers, particularly those that are active in the adipose tissue and T cells of the immune system (Silvert et al., 2019). Collectively, all these studies highlight the adaptive potential of admixture with other hominins, which had also adapted to their environment, and reveal that Neanderthals did indeed pass on to early Europeans key mutations for controlling the immune response.

Immunology, human genetics and precision medicine

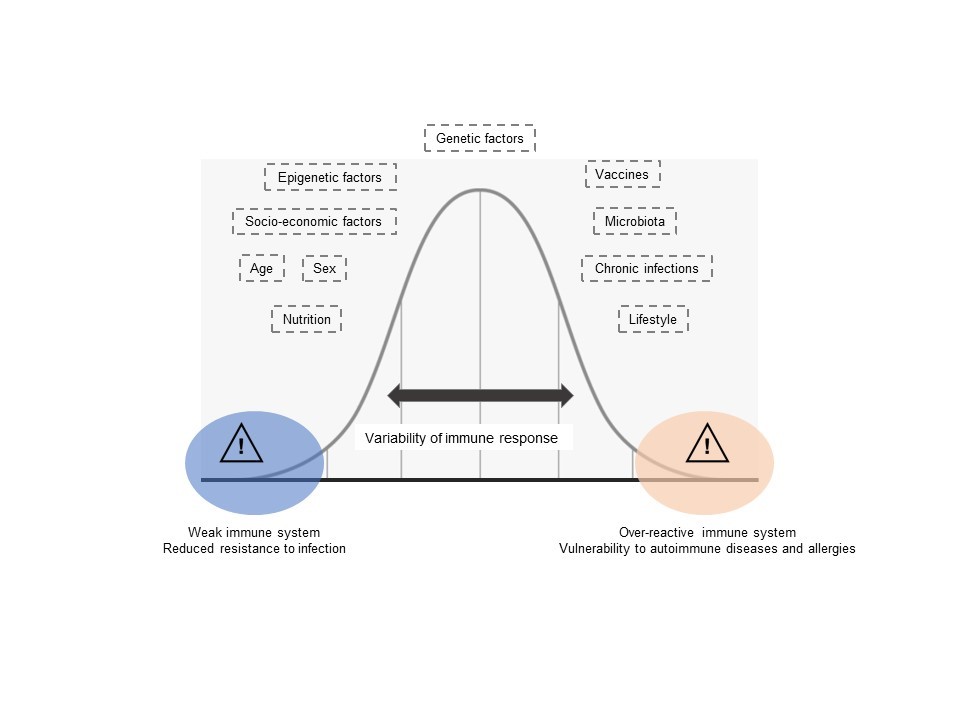

The third strand of our research, which began in the early 2010s, concerns the link between human immunology, genetics, and precision medicine. Our aim is to gain a better understanding of how genetic diversity, on the one hand, and non-genetic factors such as sex, age, nutrition, microbiota, epigenetic factors and lifestyle, on the other, can alter our immune responses (Fig. 7). In the long term, this information could pave the way to treatments that are better adapted to individuals and are more effective, with fewer side effects.

Study of systems immunology. Various heritable and non-heritable factors contribute to the diversity of the immune response between individuals and populations. Some of these factors can lead to an immune response that is “weaker”, resulting in decreased protection against infection. Conversely, other factors can lead to an over-reactive immune response, which protects better against infection but can also the risk of developing autoimmune, inflammatory or allergic diseases.

The study of the genetic architecture of gene expression, through the characterization of expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs), has revealed its full value in establishing links between genetic diversity, intermediate phenotypes such as gene expression, and ultimate phenotypes such as susceptibility to infection (Dermitzakis, 2012; Fairfax and Knight, 2014). In recent years, we have started several projects involving the use of expression data, whether from protein-coding genes or small regulatory RNAs, combined with a model of immune activation, such as the infection of cells by infectious agents like the tuberculosis bacillus or influenza virus (Quach et al., 2016; Rotival et al., 2019; Siddle et al., 2014; Siddle et al., 2015). These studies should ultimately help us to better understand how variation in immune phenotypes has contributed to human adaptation to pathogen pressures.

For example, we characterized the transcriptional responses of monocytes to different bacterial and viral stimuli in individuals of African and European ancestry, all living in Belgium, in order to homogenize environmental exposure as much as possible (Quach et al., 2016). We have shown that there is indeed population differences: Africans and Europeans differ in the magnitude and extent of their immune response, particularly for certain genes involved in inflammatory and antiviral responses. These differences are largely due to genetic variants that modulate gene expression and that present different frequencies between the two populations. This work has also shown that natural selection may have favoured some of these mutations, leading each of these populations to better adaptation. Interestingly, through independent processes, selection favoured the same immune phenotype in Africans and Europeans: a reduction of the inflammatory response. This example of “convergent evolution” supports the notion that an overly strong immune response, as in the case of autoimmune diseases or allergies, should be avoided, even if it provides effective protection against infection.

In a more general context, identifying the various genetic and non-genetic factors behind the variability of the immune system is the core of the “Milieu intérieur” consortium, which I have been coordinating since 2011, first with Matthew Albert and then with Darragh Duffy (Thomas et al., 2015). This project brings together the multidisciplinary expertise of researchers in the fields of immunology, human and quantitative genetics, microbiology and computational biology. It takes its name from the concept of “internal environment”, developed by the physiologist and founder of experimental medicine, Claude Bernard, according to whom the internal environment – that is, the main internal fluids essential for living organisms – governs the very principles of life. The aim of this project is to establish the parameters that characterize the immune system of healthy individuals, paving the way for precision medicine.

To this end, we have recruited a cohort of 1,000 healthy individuals, which includes 500 women and 500 men, stratified by age classes between 20 and 70 years (Thomas et al., 2015). In recent years, we have obtained a large number of immune phenotypes, including the characterization of the proportions of immune cells in the blood, the gene and protein expression of hundreds of genes after stimulation by around thirty immune stimuli, and the characterization of faecal and nasal microbiota (Duffy et al., 2014; Patin et al., 2018; Piasecka et al., 2018; Scepanovic et al., 2019; Urrutia et al., 2016). In addition, a large number of health parameters, serologies for chronic infections (CMV, EBV, influenza, Helicobacter pylori, toxoplasmosis, etc.), vaccination and medical histories, socio-economic and lifestyle variables have been obtained, including diet, smoking habits, sports activities, sleep quality, and so on (Thomas et al., 2015).

Let me share with you two examples of this work. First, we focused on studying the factors driving the variability of cell types circulating in the blood (Patin et al., 2018). For this, we used flow cytometry to measure a large number of immunophenotypes. Of the 140 variables tested that could explain the variability of immune cells in our blood, only five had a real impact: human genetics, chronic cytomegalovirus infection, smoking, age and sex. Secondly, we showed that genetic factors influence primarily the variability of cell populations of the innate immune system, while non-genetic factors mostly affect cell variability of the adaptive immune system.

The second study investigated the factors driving the variability of the immune response to some infectious agents, such as the bacteria Escherichia coli, staphylococcus aureus, BCG (often used as a vaccine against tuberculosis), the influenza virus, or the fungus Candida albicans (Piasecka et al., 2018). Our study of the 1,000 individuals revealed that about 10% of the variance in immune response was explained by the cumulative effects of genetics, while sex and age accounted for about 5% of the total variance.

Although our understanding of the genetic, intrinsic, and environmental sources of immune response variation is growing, a significant proportion of inter-individual immune variance remains unexplained. Further research is therefore needed, which will take into account more complex forms of genetic control, such as the role of epistatic interactions or rare variants, interactions with age and sex, and the impact of the environment on gene expression, all using cutting-edge technologies such as single-cell sequencing.

The future of evolutionary biology: an ode to diversity

In conclusion, ladies and gentlemen, genomic approaches, combined with the principles and models developed in population genetics, have enabled us to identify key, essential immune functions and to distinguish them from others presenting higher levels of immunological redundancy. Genes whose variation has been beneficial to the survival of our species have also been identified, some of which harbour mutations that have been acquired through admixture with both archaic humans and between modern populations. Nevertheless, there are still many links to be explored between population genetics and evolution, on the one hand, and human immunology, on the other. This is the case not only for the effects of natural selection on immune phenotypes and disease risk at various time-scales, but also for the way in which adaptation to fight infection in the past can, following environmental or lifestyle changes, lead to “maladaptation” and, consequently, to pathology.

The study of ancient DNA from humans who have lived before or after major events, such as the transition to sedentary, farming-based lifestyles or epidemics that, like the plague, wiped out millions of people over the last millennium, could help us to better understand the factors underlying the susceptibility to, or severity of, infectious diseases. New statistical methods also need to be developed to identify more subtle forms of natural selection, such as polygenic selection and even polygenic introgression, which are still difficult to detect.

Finally, it should be pointed out that most genomic studies focus on large continental populations. By way of comparison, populations of European ancestry represent only 16% of the world’s inhabitants, whereas they make up more than 78% of the categories taken into account in genetic studies (Sirugo et al., 2019). For both scientific and societal reasons, it is therefore time to include more populations of non-European ancestry in these genomic studies, particularly the so-called “neglected” populations, in order to improve the representation of human genetic diversity as a whole. These multidisciplinary efforts, including approaches based on population genetics, functional genomics and genetic epidemiology, are needed to shed light on the links between migration history, natural selection, cultural factors and disease.

But it is time to return to the notion of diversity, a subject that has fascinated me since childhood. I am a Parisian, but also a Catalan, a Spaniard, a Frenchman, and above all, a European. This attraction to the diversity of languages, cultures and individuals led me, I believe, to population genetics, a discipline that is an ode to plurality, travel and diversity. It is diversity, and diversity alone, in fact, that drives evolution and underpins our species adaptation to environmental changes. As I hope to have shown you in this inaugural lecture, and as I will be going into in greater depth throughout my lectures, the study of genetic diversity makes it possible to answer key questions in evolutionary biology – questions that have major repercussions on human health.

If there is any merit in our experimental approach, it is that it seeks to unveil the most imposing and immediate experience that has ever existed: that of Nature.

Abi-Rached Laurent, Jobin Matthew J., Kulkarni Subhash, McWhinnie Alasdair, Dalva Klara, Gragert Loren, Babrzadeh Farbod, Gharizadeh Baback, Luo Ma, Plummer Francis A. et al., “The shaping of modern human immune systems by multiregional admixture with archaic humans”, Science, vol. 334, 2011, pp. 89-94, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1209202.Alcais Alexandre, Quintana-Murci Lluis, Thaler David S., Schurr Erwin, Abel Laurent and Casanova Jean-Laurent, “Life-threatening infectious diseases of childhood: single-gene inborn errors of immunity?”, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 2010, pp. 18-33, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05834.x.Allison A.C., “Protection afforded by sickle-cell trait against subtertian malareal infection”, British Medical Journal, vol. 1, 1954, pp. 290-294.Auton Adam, Brooks Lisa D., Durbin Richard M., Garrison Erik P., Kang Hyun Min, Korbel Jan O., Marchini Jonathan L., McCarthy Shane, McVean Gil A. and Abecasis Gonçalo R., “A global reference for human genetic variation”, Nature, vol. 526, 2015, pp. 68-74, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature15393.Bach Jean-François, “The effect of infections on susceptibility to autoimmune and allergic diseases”, New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 347, 2002, pp. 911-920, https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmra020100.Barreiro Luis B., Laval Guillaume, Quach Hélène, Patin Étienne and Quintana-Murci Lluis, “Natural selection has driven population differentiation in modern humans”, Nature Genetics, vol. 40, 2008, pp. 340-345, https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.78.Barreiro Luis B., Ben-Ali Meriem, Quach Hélène, Laval Guillaume, Patin Étienne, Pickrell Joseph K., Bouchier Christiane, Tichit Magali, Neyrolles Olivier, Gicquel Brigitte et al., “Evolutionary dynamics of human Toll-like receptors and their different contributions to host defense”, PLoS Genetics, vol. 5, 2009, e1000562, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1000562.Barreiro Luis B. and Quintana-Murci Lluis, “From evolutionary genetics to human immunology: how selection shapes host defence genes”, Nature Reviews Genetics, vol. 11, 2010, pp. 17-30, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg2698.Behar Doron M., Harmant Christine, Manry Jeremy, van Oven Mannis, Haak Wolfgang, Martinez-Cruz Begoña, Salaberria Jasone, Oyharcabal Bernard, Bauduer Frédéric, Comas David et al., “The Basque paradigm: genetic evidence of a maternal continuity in the Franco-Cantabrian region since pre-Neolithic times”, American Journal of Human Genetics, vol. 90, 2012, pp. 486-493, https://doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.ajhg.2012.01.002.Brinkworth Jessica F. and Barreiro Luis B., “The contribution of natural selection to present-day susceptibility to chronic inflammatory and autoimmune disease”, Current Opinion in Immunology, vol. 31, 2014, pp. 66-78, https://doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.coi.2014.09.008.Cairns John, Matters of Life and Death, Princeton (New Jersey), Princeton University Press, 1997.Casanova Jean-Laurent and Abel Laurent, “Inborn errors of immunity to infection: the rule rather than the exception”, Journal of Experimental Medicine, vol. 202, 2005, pp. 197-201.Casanova Jean-Laurent, Abel Laurent and Quintana-Murci Lluis, “Immunology taught by human genetics”, Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantative Biology, vol. 78, 2013, pp. 157-172, http://symposium.cshlp.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/sqb.2013.78.019968.Cavalli-Sforza Luigi Luca, African Pygmies, New York, Academic Press, 1986.Dannemann Michael and Racimo Fernando, “Something old, something borrowed: admixture and adaptation in human evolution”, Current Opinion in Genetics & Development, vol. 53, 2018, pp. 1-8, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gde.2018.05.009.Dermitzakis Emmanouil T., “Cellular genomics for complex traits”, Nature Reviews Genetics, vol. 13, 2012, pp. 215-220, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg3115.Deschamps Matthieu, Laval Guillaume, Fagny Maud, Itan Yuval, Abel Laurent, Casanova Jean-Laurent, Patin Étienne, and Quintana-Murci Lluis, “Genomic signatures of selective pressures and introgression from archaic hominins at human innate immunity genes”, American Journal of Human Genetics, vol. 98, 2016, pp. 5-21, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.11.014.Diamond Jared and Bellwood Peter “Farmers and their languages: the first expansions”, Science, vol. 300, 2003, pp. 597-603, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1078208.Duffy Darragh, Rouilly Vincent, Libri Valentina, Hasan Milena, Beitz Benoit, David Mikael, Urrutia Alejandra, Bisiaux Aurélie, Labrie Samuel T., Dubois Annick et al., “Functional analysis via standardized whole-blood stimulation systems defines the boundaries of a healthy immune response to complex stimuli”, Immunity, vol. 40, 2014, pp. 436-450, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2014.03.002.Enard David and Petrov Dimitri A., “Evidence that RNA viruses drove adaptive introgression between neanderthals and modern humans”, Cell, vol. 175, 2018, pp. 360-371, e313, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2018.08.034.Fagny Maud, Patin Étienne, Enard David, Barreiro Luis B., Quintana-Murci Lluis and Laval Guillaume, “Exploring the occurrence of classic selective sweeps in humans using whole-genome sequencing data sets”, Molecular Biology and Evolution, vol. 31, 2014, pp. 1850-1868, https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msu118.Fagny Maud, Patin Étienne, MacIsaac Julia L., Rotival Maxime, Flutre Timothée, Jones Meaghan J., Siddle Katherine J., Quach Hélène, Harmant Christine, McEwen Lisa M. et al., “The epigenomic landscape of African rainforest hunter-gatherers and farmers”, Nature Communications, vol. 6, 2015, 10047, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10047.Fairfax Benjamin P. and Knight Julian C., “Genetics of gene expression in immunity to infection”, Current Opinion in Immunology, vol. 30, 2014, pp. 63-71, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coi.2014.07.001.Fan Shaohua, Hansen Matthew E.B., Lo Yancy and Tishkoff Sarah A., “Going global by adapting local: a review of recent human adaptation”, Science, vol. 354, 2016, pp. 54-59, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaf5098.Haldane John Burdon Sanderson, “Disease and evolution”, Ricerca Scientifica, vol. 19 (suppl. A), 1949, pp. 68-76.Hellenthal Garrett, Busby George B.J., Band Gavin, Wilson James F., Capelli Cristian, Falush Daniel and Myers Simon, “A genetic atlas of human admixture history”, Science, vol. 343, 2014, pp. 747-751, https://doi.org/10.1126%2Fscience.1243518.Henn Brenna M., Botigue Laura R., Bustamante Carlos D., Clark Andrew G. and Gravel Simon, “Estimating the mutation load in human genomes”, Nature Reviews Genetics, vol. 16, 2015, pp. 333-343, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg3931.Huerta-Sanchez Emilia, Jin Xin, Asan, Bianba Zhuoma, Peter Benjamin M., Vinckenbosch Nicolas, Liang Yu, Yi Xin, He Mingze, Somel Mehmet et al., “Altitude adaptation in Tibetans caused by introgression of Denisovan-like DNA”, Nature, vol. 512, 2014, pp. 194-197, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13408.Husquin Lucas T., Rotival Maxime, Fagny Maud, Quach Hélène, Zidane Nora, McEwen Lisa M., MacIsaac Julia L., Kobor Michael S., Aschard Hugues, Patin Étienne. et al., “Exploring the genetic basis of human population differences in DNA methylation and their causal impact on immune gene regulation”, Genome Biology, vol. 19, 2018, p. 222, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-018-1601-3.Jeong Choongwon and Di Rienzo Anna, “Adaptations to local environments in modern human populations”, Current Opinion in Genetics & Development, vol. 29, 2014, pp. 1-8, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gde.2014.06.011.Kimura Motoo, “Evolutionary rate at the molecular level”, Nature, vol. 217, 1968, pp. 624-626.Laso-Jadart Romuald, Harmant Christine, Quach Hélène, Zidane Nora, Tyler-Smith Chris, Mehdi Qasim, Ayub Qasim, Quintana-Murci Lluis and Patin Étienne, “The genetic legacy of the Indian Ocean slave trade: recent admixture and post-admixture selection in the of Pakistan”, American Journal of Human Genetics, vol. 101, no. 6, 2017, pp. 977-984, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.09.025.Laval Guillaume, Peyregne Stéphane, Zidane Nora, Harmant Christine, Renaud François, Patin Étienne, Prugnolle Franck and Quintana-Murci Lluis, “Recent adaptive acquisition by rainforest hunter-gatherers of the late Pleistocene sickle-cell mutation suggests past ecological differences in exposure to Malaria in Africa”, American Journal of Human Genetics, vol. 104, no. 3, 2019, pp. 553-561, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2019.02.007.Leonardi Michela, Librado Pablo, Der Sarkissian Clio, Schubert Mikkel, Alfarhan Ahmed H., Alquraishi Saleh A., Al-Rasheid Khaled A.S., Gamba Cristina, Willerslev Eske and Orlando Ludovic, “Evolutionary patterns and processes: lessons from ancient DNA”, Systematic Biology, vol. 66, no. 1, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1093%2Fsysbio%2Fsyw059.Lohmueller Kirk E., “The distribution of deleterious genetic variation in human populations”, Current Opinion in Genetics & Development, vol. 29, 2014, pp. 139-146.Lopez Marie, Kousathanas Athanasios, Quach Hélène, Harmant Christine, Mouguiama-Daouda Patrick, Hombert Jean-Marie, Froment Alain, Perry George H., Barreiro L.B., Verdu Paul. et al., “The demographic history and mutational load of African hunter-gatherers and farmers”, Nature Ecology & Evolution, vol. 2, 2018, pp. 721-730, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0496-4.Lopez Marie, Choin Jeremy, Sikora Martin, Siddle Katherine, Harmant Christine, Costa Helio A., Silvert Martin, Mouguiama-Daouda Patrick, Hombert Jean-Marie, Froment Alain et al., “Genomic evidence for local adaptation of hunter-gatherers to the African rainforest”, Current Biology, vol. 29, 2019, pp. 2926-2935, e2924, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2019.07.013.Manry Jérémy, Laval Guillaume, Patin Étienne, Fornarino Simona, Itan Yuval, Fumagalli Matteo, Sironi Manuela, Tichit Magali, Bouchier Christiane, Casanova Jean Laurent et al., “Evolutionary genetic dissection of human interferons”, Journal of Experimental Medicine, vol. 208, 2011, pp. 2747-2759, https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20111680.Nielsen Rasmus, Akey Joshua M., Jakobsson Mattias, Pritchard Jonathan K., Tishkoff Sarah and Willerslev Eske, “Tracing the peopling of the world through genomics”, Nature, vol. 541, 2017, pp. 302-310, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature21347.Novembre John, Johnson Toby, Bryc Katarzyna, Kutalik Zoltán, Boyko Adam R., Auton Adam, Indap Amit, King Karen S., Bergmann Sven, Nelson Matthew R. et al., “Genes mirror geography within Europe”, Nature, vol. 456, 2008, pp. 98-101, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07331.Novembre John and Di Rienzo Anna Maria, “Spatial patterns of variation due to natural selection in humans”, Nature Reviews Genetics, vol. 10, 2009, pp. 745-755, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg2632.Patin Étienne, Laval Guillaume, Barreiro Luis B., Salas Antonio, Semino Ornella, Santachiara-Benerecetti Silvana, Kidd Kenneth K., Kidd Judith R., Van derVeen Lolke, Hombert Jean-Marie et al., “Inferring the demographic history of African farmers and pygmy hunter-gatherers using a multilocus resequencing data set”, PLoS Genetics, vol. 5, 2009, e1000448, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1000448.Patin Étienne, Siddle Katherine J., Laval Guillaume, Quach Hélène, Harmant Christine, Becker Noémie, Froment Alain, Regnault Béatrice, Lemée Laure, Gravel Simon et al., “The impact of agricultural emergence on the genetic history of African rainforest hunter-gatherers and agriculturalists”, Nature Communications, vol. 5, 2014, art. 3163, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms4163.Patin Étienne, Lopez Marie, Grollemund Rebecca, Verdu Paul, Harmant Christine, Quach Hélène, Laval Guillaume, Perry George H., Barreiro Luis B., Froment Alain et al., “Dispersals and genetic adaptation of Bantu-speaking populations in Africa and North America”, Science, vol. 356, 2017, pp. 543-546, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aal1988.Patin Étienne, Hasan Milena, Bergstedt Jacob, Rouilly Vincent, Libri Valentina, Urrutia Alejandra, Alanio Cécile, Scepanovic Petar, Hammer Christian, Jonsson Friederike. et al., “Natural variation in the parameters of innate immune cells is preferentially driven by genetic factors”, Nature Immunology, vol. 19, 2018, pp. 302-314, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41590-018-0049-7.Patin Étienne and Quintana-Murci Lluis, “The demographic and adaptive history of central African hunter-gatherers and farmers”, Current Opinion in Genetics & Development, vol. 53, 2018, pp. 90-97, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gde.2018.07.008.Phillipson David W., “The chronology of the Iron Age in Bantu Africa”, The Journal of African History, vol. 16, no. 3, 1975, pp. 321-342, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021853700014298.Piasecka Barbara, Duffy Darragh, Urrutia Alejandra, Quach Hélène, Patin Étienne, Posseme Céline, Bergstedt Jacob, Charbit Bruno, Rouilly Vincent, MacPherson Cameron R. et al., “Distinctive roles of age, sex, and genetics in shaping transcriptional variation of human immune responses to microbial challenges”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 115, 2018, E488-E497, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1714765115.Quach Hélène, Rotival Maxime, Pothlichet Julien, Loh Yong-Hwee Eddie, Dannemann Michael, Zidane Nora, Laval Guillaume, Patin Étienne, Harmant Christine, Lopez Marie et al., “Genetic adaptation and neandertal admixture shaped the immune system of human populations”, Cell, vol. 167, 2016, pp. 643-656, e617, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.09.024.Quach Hélène and Quintana-Murci Lluis, “Living in an adaptive world: genomic dissection of the genus Homo and its immune response”, Journal of Experimental Medecine, vol. 214, 2017, pp. 877-894, https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20161942.Quintana-Murci Lluis, Semino Ornella, Bandelt Hans-J., Passarino Giuseppe, McElreavey Ken and Santachiara-Benerecetti A. Silvana, “Genetic evidence of an early exit of Homo sapiens sapiens from Africa through eastern Africa”, Nature Genetics, vol. 23, 1999, pp. 437-441, http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/70550.Quintana-Murci Lluis, Chaix Raphaëlle, Wells R. Spencer, Behar Doron M., Sayar Hamid, Scozzari Rosaria, Rengo Chiara, Al-Zahery Nadia, Semino Ornella, Santachiara-Benerecetti A.S. et al., “Where West meets East: the complex mtDNA landscape of the southwest and Central Asian corridor”, American Journal of Human Genetics, vol. 74, 2004, pp. 827-845, https://doi.org/10.1086%2F383236.Quintana-Murci Lluis and Clark Andrew G., “Population genetic tools for dissecting innate immunity in humans”, Nature Reviews Immunology, vol. 13, 2013, pp. 280-293, https://doi.org/10.1038/nri3421.Quintana-Murci Lluis, “Understanding rare and common diseases in the context of human evolution”, Genome Biology, vol. 17, 2016, p. 225, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-016-1093-y.Quintana-Murci Lluis, “Human immunology through the lens of evolutionary genetics”, Cell, vol. 177, 2019, pp. 184-199, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2019.02.033.Racimo Fernando, Sankararaman Sriram, Nielsen Rasmus and Huerta-Sanchez Emilia, “Evidence for archaic adaptive introgression in humans”, Nature Reviews Genetics, vol. 16, 2015, pp. 359-371, https://doi.org/10.1038%2Fnrg3936.Rotival Maxime, Quach Hélène and Quintana-Murci Lluis “Defining the genetic and evolutionary architecture of alternative splicing in response to infection”, Nature Communications, vol. 10, 2019, p. 1671, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09689-7.Sankararaman Sriram, Mallick Swapan, Dannemann Michael, Prufer Kay, Kelso Janet, Paabo Svante, Patterson Nick and Reich David, “The genomic landscape of Neanderthal ancestry in present-day humans”, Nature, vol. 507, 2014, pp. 354-357, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12961.Scepanovic Petar, Hodel Flavia, Mondot Stanislas, Partula Valentin, Byrd Allyson, Hammer Christian, Alanio Cécile, Bergstedt Jacob, Patin Étienne, Touvier Mathilde et al., “A comprehensive assessment of demographic, environmental, and host genetic associations with gut microbiome diversity in healthy individuals”, Microbiome, vol. 7, 2019, p. 130, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-019-0747-x.Siddle Katherine J., Deschamps Matthieu, Tailleux Ludovic, Nedelec Yohann, Pothlichet Julien, Lugo-Villarino Geanncarlo, Libri Valentina, Gicquel Brigitte, Neyrolles Olivier, Laval Guillaume et al., “A genomic portrait of the genetic architecture and regulatory impact of microRNA expression in response to infection”, Genome Research, vol. 24, 2014, pp. 850-859, https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.161471.113.Siddle Katherine J. and Quintana-Murci Lluis, “The Red Queen’s long race: human adaptation to pathogen pressure”, Current Opinion in Genetics & Development, vol. 29, 2014, pp. 31-38, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gde.2014.07.004.Siddle Katherine J., Tailleux Ludovic, Deschamps Matthieu, Loh Yong-Hwee Eddie, Deluen Cécile, Gicquel Brigitte, Antoniewski Christophe, Barreiro Luis B., Farinelli Laurent and Quintana-Murci Lluis, “Bacterial infection drives the expression dynamics of microRNAs and their isomiRs”, PLoS Genetics, vol. 11, 2015, e1005064, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1005064.Silvert Martin, Quintana-Murci Lluis and Rotival Maxime, “Impact and evolutionary determinants of Neanderthal introgression on transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation”, American Journal of Human Genetics, vol. 104, 2019, pp. 1241-1250, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2019.04.016.Sirugo Giorgio, Williams Scott M. and Tishkoff Sarah A., “The missing diversity in human genetic studies”, Cell, vol. 177, 2019, pp. 26-31, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2019.02.048.Skoglund Pontus and Mathieson Iain, “Ancient genomics of modern humans: the first decade”, Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics, vol. 19, 2018, pp. 381-404, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-genom-083117-021749.Smith Zachary D. and Meissner Alexander, “DNA methylation: roles in mammalian development”, Nature Reviews Genetics, vol. 14, 2013, pp. 204-220, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg3354.Stoneking Mark and Krause Johannes, “Learning about human population history from ancient and modern genomes”, Nature Reviews Genetics, vol. 12, 2011, pp. 603-614, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg3029.Strachan D.P. “Hay fever, hygiene, and household size”, British Medical Journal, vol. 299, 1989, pp. 1259-1260, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.299.6710.1259.Thomas Stéphanie, Rouilly Vincent, Patin Étienne, Alanio Cécile, Dubois Annick, Delval Cécile, Marquier Louis-Guillaume, Fauchoux Nicolas, Sayegrih Seloua, Vray Muriel et al., “The Milieu intérieur study – an integrative approach for study of human immunological variance”, Clinical Immunology, vol. 157, no. 2, 2015, pp. 277-293, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2014.12.004.Tishkoff Sarah A., Reed Floyd A., Ranciaro Alessia, Voight Benjamin F., Babbitt Courtney C., Silverman Jesse S., Powell Kweli, Mortensen Holly M., Hirbo Jibril B., Osman Maha et al., “Convergent adaptation of human lactase persistence in Africa and Europe”, Nature Genetics, vol. 39, 2007, pp. 31-40, https://doi.org/10.1038/ng1946.Urrutia Alejandra, Duffy Darragh, Rouilly Vincent, Posseme Céline, Djebali Raouf, Illanes Gabriel, Libri Valentina, Albaud Benoit, Gentien David, Piasecka Barbara et al., “Standardized whole-blood transcriptional profiling enables the deconvolution of complex induced immune responses”, Cell Reports, vol. 16, 2016, pp. 2777-2791, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2016.08.011.Vasseur Estelle, Boniotto Michele, Patin Étienne, Laval Guillaume, Quach Hélène, Manry Jeremy, Crouau-Roy Brigitte and Quintana-Murci Lluis, “The evolutionary landscape of cytosolic microbial sensors in humans”, American Journal of Human Genetics, vol. 91, 2012, p. 27-37, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.05.008.Vitti Joseph J., Grossman Sharon R. and Sabeti Pardis C., “Detecting natural selection in genomic data”, Annual Review of Genetics, vol. 47, 2013, pp. 97-120, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-genet-111212-133526.- Darwin and Mendel: the origins of population genetics

- Human genome sequencing and the quest for diversity

- Human migration and natural selection

- A long history of archaic and modern admixture

- The history of Homo sapiens through the lens of evolutionary genetics

- Study of the demographic history of human populations

- Modes of subsistence, migrations and adaptation to the environment

- Reacting to the environment: epigenetics in human populations

- Humans and microbes: a double-edged relationship

- Natural selection, innate immunity and collateral damage

- Neanderthal ancestry and antiviral responses

- Immunology, human genetics and precision medicine

- The future of evolutionary biology: an ode to diversity

Leonardo da Vinci, The Virgin, the

Child Jesus and Saint Anne, Saint John the

Baptist, and the Mona Lisa, 16th century, oil on wood, Musée du Louvre, Department

of Paintings.

Leonardo da Vinci, The Virgin, the

Child Jesus and Saint Anne, Saint John the

Baptist, and the Mona Lisa, 16th century, oil on wood, Musée du Louvre, Department

of Paintings. The major human migrations across the planet:

approximate habitat areas of Neanderthals and Denisovans. The

expansion of the Bantu-speaking peoples, which began around

4,000-5,000 years ago, is indicated by arrows on the African

continent.

The major human migrations across the planet:

approximate habitat areas of Neanderthals and Denisovans. The

expansion of the Bantu-speaking peoples, which began around

4,000-5,000 years ago, is indicated by arrows on the African